This article was originally published in California Health Law News

Executive Summary: This article provides an in-depth exploration of the nuanced interaction between Private Equity (PE) investments and medical group practices within the legal framework of California’s prohibition against the Corporate Practice of Medicine (CPOM). It critically analyzes the doctrine’s current application in California’s healthcare sector and its impact on the operational dynamics of medical practices post-PE acquisition. Moreover, the discussion extends to innovative structuring strategies that PE firms and healthcare practices can employ to align their operations with CPOM compliance while achieving their business objectives.

Understanding Private Equity Acquisitions and Recent Trends

In the past decade, there has been a remarkable surge in private equity (PE) firm involvement within the healthcare sector. PE firms have acquired a diverse range of healthcare facilities, effectively encompassing the entire spectrum of healthcare services. Independent physician medical practices have emerged as particularly attractive targets for these investments. PE acquisitions of physician practices rose from 75 deals in 2012 to 484 in 2021.1 This flood of PE healthcare acquisitions has contributed over $1 trillion in investments in the past decade.2

PE firms harness capital from high-net-worth individuals and institutions, often leveraging significant debt, to purchase companies. These firms typically aim for a rapid exit within three to five years and expect substantial profits.3 In fragmented markets, PE firms frequently adopt a strategy of making an “anchor investment” by initially acquiring a “platform practice,” which serves as a base for further acquisitions and consolidation within a specific region.4 A key characteristic of PE investments is their direct management involvement in the companies they acquire, frequently implementing changes to enhance valuation and future profitability prospects.5

The growing prevalence of PE ownership in healthcare has generated diverging opinions within the medical community. Critics argue that PE firms’ profit-centric approach compromises patient safety, saddles healthcare entities with excessive debt, and disrupts care through continuous management alterations and frequent sell-offs. In contrast, supporters of PE ownership highlight the injection of capital, managerial expertise, operational efficiency improvements, economies of scale, and the potential to align profit motives with the delivery of high-quality care. PE investments can also provide crucial capital and financial stability for medical groups seeking autonomy.

These converging opinions are further intensified by the distinctive nature of PE compared to other health services investments—the primary distinguishing factor being that PE firms are comprised of lay investors who are not bound by the same professional considerations as healthcare providers.6 Thus, the concern is that the PE investors’ interests conflict with healthcare providers’ duties to prioritize patient safety. This sentiment is consistent with the foundational principles of the prohibition on the corporate practice of medicine (CPOM), a legal principle enforced by several states, including California. The CPOM prohibition, sometimes called the corporate bar (on the practice of medicine), aims to prevent non-physicians from exerting undue influence over medical practices, thereby safeguarding the physician-patient relationship against commercial exploitation. As PE firms increasingly seek to acquire medical group practices, California’s CPOM prohibition acts as a critical checkpoint.

Legal Framework and Practical Considerations

California’s CPOM Doctrine

In the simplest terms, California’s CPOM doctrine prohibits non-physicians from owning or exercising control over medical practices. California’s corporate bar is designed to protect the clinical independence of physicians. It aims to ensure that medical decisions are made based on the patient’s best interests and not influenced by business considerations of non-physician owners or managers.

California’s CPOM prohibition is codified in two primary statutes:

- Business and Professions Code section 2052 prohibits the unlicensed practice, attempted practice, or advertisement of practice of medicine in California, and makes these acts a misdemeanor. Importantly, the statute restricts medical practice to those who are duly licensed.

- Business and Professions Code section 2400 explicitly prohibits corporations and other artificial legal entities from practicing medicine or employing physicians to provide professional medical services. This statute seeks to ensure that medical decisions are made by licensed medical professionals rather than corporate entities.

Key to carrying out California’s CPOM prohibition is the limitation on the corporate form available to medical practices. If medical practices want to incorporate, they must do so as professional medical corporations (PCs).7 With limited exceptions, licensed physicians must own and control these PCs.8 As such, a PE firm cannot purchase a medical practice outright.9

Friendly-PC Arrangements – the Typical Form

Despite California’s general prohibition, a corporate and contractual structure has been utilized to allow non-physicians to be involved in certain non-clinical aspects of a medical practice. This structure is often referred to as the “friendly-PC model,” and crucially, in return for providing non-clinical services, non-physicians are able to capture a portion of the medical group’s revenue.

Under the friendly-PC model, the lay entity owns a management services organization (MSO) (sometimes called an administrative services organization), which contracts with a PC through a management services agreement. The PC is solely owned and governed by a licensed physician who is “friendly” to the MSO.

The management services agreement entrusts the MSO with exclusive oversight of the administrative and managerial aspects of the PC in exchange for a management fee paid by the PC to the MSO. In this arrangement, the MSO manages all non-clinical and operational facets, including owning leases and equipment and employing non-clinical staff. The MSO collects a management fee from the PC, which could be a flat monthly fee, based on a percentage of the PC’s revenues, or a combination of the two. Importantly, however, the management fee must be commensurate with the MSO’s services, equipment, or facilities rendered and cannot equate to a sharing of the practice’s profits.10

This connection between the PC and MSO is often reinforced through a succession agreement. A succession agreement allows the MSO to appoint a new shareholder to the PC in response to specific events, such as an attempt by the physician to terminate the management services agreement. Often, the MSO can freely eject the friendly physician without cause. Because the MSO essentially has the power to eject the friendly physician via the succession agreement, the MSO maintains a certain level of control over the PC’s operations.

Friendly-PC Arrangement in the Context of a PE Acquisition

In the PE context, the PE firm will first form (or cause the PC to form) the MSO. Next, the friendly physician will cause the PC to transfer and assign its non-clinical assets to the MSO, including, where appropriate, the PC’s goodwill. In exchange for the PC’s non-clinical assets, the MSO will pay the PC a considerable amount of cash and issue rollover equity in the MSO or the MSO’s parent entity. The purchase price is financed through debt secured against the acquired entity itself.11 Some PE firms secure loans using their healthcare facilities as collateral, repaying investors quickly while the facilities assume the debt. They also sell healthcare assets to other investors, using the proceeds for returns and then leasing the assets back to the healthcare organizations.12

Simultaneously, or soon thereafter, the PC will be reorganized so that it is solely owned and operated by the friendly physician. If the PC has more than one shareholder, the PC will cause the redemption of all shareholders other than the friendly physician. The MSO, PC, and friendly physician then enter into the management services and succession agreements, as applicable.

Finally, the parties’ purchase agreement often requires the PC to deliver executed professional services agreements (i.e., independent contractor or employment agreements) for each of its contracted providers before closing. The MSO wants to ensure that the PC’s providers will continue treating their patients as they did immediately before closing.

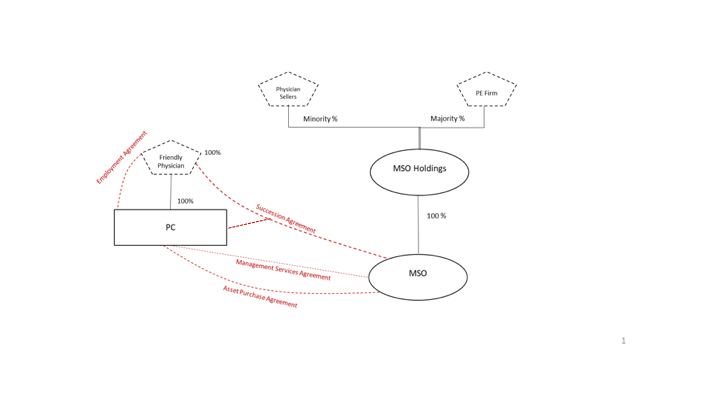

The diagram below illustrates a simplified version of the relationships between the various entities post-close.

Other considerations in these deals concern the ownership and control of the MSO and, more specifically, how the MSO’s profits are eventually distributed to the MSO’s owners. Post-close, the PE firm holds a majority stake in the MSO (or its parent), while the physician sellers collectively own a minority stake. The owners’ rights (and ability to control the MSO) will depend on the approval rights allocated to minority interest holders under the governance documents of the MSO or its holding company.13

PE Healthcare Acquisition Impacts and Legal Responses

Impact of PE Acquisitions on Quality, Cost, and Accessibility of Healthcare

The impact of PE healthcare acquisitions is the subject of ongoing debate. PE backers and supporters alike have documented important benefits to PE healthcare acquisitions, including:

- Funding innovation and streamlining costs, especially in critical areas like telehealth and healthcare IT.14

- Supporting clinical trials and unlocking lifesaving treatments like mRNA vaccinations15.

- Helping consolidate medical groups’ market power and obtain favorable reimbursement rates16.

- Offering healthcare providers a source of capital and relieving them of management responsibilities.17

- Significant upfront cash payments that are much more than traditional asset purchase transactions proposed by other health systems.18

Critics often raise concerns about the prioritization of profit over patient care, potential reductions in the range of services offered to maximize profitability, and the long-term sustainability of such investments. Studies have found that this profit-centric approach has led to:

- An average increase of $71 (+20.2%) in charges per claim following PE acquisition.19

- An increase of $23 (+11.0%) in the allowed amount per claim.20

- An increase in overutilization of services and increased spending without commensurate patient benefits, raising important considerations for policymakers.21

- A higher clinician replacement ratio compared to non-PE-acquired practices.22

- Statistically significant per-patient expenditure increases for private physician practices.23

- An increase in patient falls, infection, and other forms of harm during hospital stay after a PE acquisition.24

In sum, while there are operational efficiencies, the focus on profit margins can sometimes lead to cost-cutting measures that can negatively affect patient care and employee satisfaction.

Legal and Regulatory Responses to PE Healthcare Acquisitions

California’s government bodies have been paying closer attention to the increasing trend of PE investments in healthcare, responding with heightened scrutiny and regulatory measures.

In 2020, the California Legislature considered Senate Bill 977,25 which aimed to grant the California Attorney General greater oversight power over healthcare transactions, including those involving PE firms. It sought to require the AG’s office to review and approve acquisitions of healthcare facilities by large health systems and private equity groups, particularly focusing on transactions that might reduce competition and increase healthcare costs. SB 977 did not pass, though a similar bill has been introduced in the current legislative session.26

In 2023, Senate Bill 184 established the Office of Health Care Affordability (“OHCA”) within the Department of Health Care Access and Information.27 OHCA adopted regulations on December 18, 2023,28 to implement the cost and market impact reviews established by Health and Safety Code section 127507 et seq. The laws obligate specific “health care entities”29 to notify OHCA about a “material change transaction”30 that could affect market competition or healthcare costs. OHCA has 60 days post-notification to decide whether to conduct a more intensive cost and market impact review of the transaction.31 If OHCA decides to conduct the review, the process may take up to eight months,32 potentially causing lengthy delays in closing. Reviews focus on market effects, service pricing, and quality, among other factors.33 Preliminary and final reports are issued, with a mandatory waiting period before transaction completion.34

OHCA’s oversight of material change transactions will likely lead to increased scrutiny of qualifying PE healthcare acquisitions. The new law’s pre-transaction notice requirements and regulatory review may deter PE firms from investing in California healthcare entities. At the very least, we anticipate that PE firms will be more cautious and selective in their California healthcare acquisitions.

Laws that may impact PE acquisition of medical practices are also developing through litigation. For example, in 2020, Allstate Insurance Company filed two complaints alleging that several radiology practices managed by Sattar Mir, who has no medical license, submitted fraudulent insurance claims.35 Among other issues, the parties disputed whether Mir’s control over medical corporations through an MSO constituted the unlicensed practice of medicine.

In its complaints, Allstate alleged that Mir illegally practiced medicine by forming and owning medical corporations, soliciting patients, selecting physicians to perform radiology services, and making decisions regarding billing and collections. After suffering dismissals in the Los Angeles County Superior Court, Allstate prevailed on appeal in August 2023. The appellate court ruled that Allstate had sufficiently alleged that Mir engaged in the unlicensed practice of medicine by exercising undue control over the radiology practices, and Allstate may, therefore, bring claims under the Insurance Fraud Prevention Act and Unfair Competition Law (UCL).36 The California Supreme Court denied the defendants’ petition for review, allowing Allstate to proceed with its lawsuits.

Challenges to the friendly-PC model have also emerged in federal court. In 2021, the American Academy of Emergency Medicine Physician Group (AAEM) sued Envision Healthcare under the UCL for allegedly using restrictive management contracts to control hundreds of medical practices.37 AAEM claimed that Envision exercised discretion over physicians’ hiring, compensation, schedules, billing, contracts with third-party payors, and ability to sell their practices. Further, Envision allegedly established clinical oversight over the physicians by establishing corporate standards of care. The Northern District of California denied Envision’s motion to dismiss the lawsuit, ruling that AAEM had sufficiently alleged that Envision violated the ban on the corporate practice of medicine.38 However, the case has been stayed because Envision filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

These recent legal developments are indicative of enhanced scrutiny of healthcare mergers and acquisitions, especially those involving PE firms. We anticipate that California’s laws governing PE investments in healthcare may become more stringent, creating increased oversight and regulation of such transactions.

Practical Considerations

Balancing Control Over the PC Post-Close

PE firms are incentivized to maintain as much control over the healthcare practice as possible. A PE firm will try to delegate to itself the most decision-making authority possible in the management services agreement. If the decision does not implicate professional medical judgment, the PE firm can contract for total control. Examples include: (1) management and administration of the non-medical aspects of the practice; (2) employment, management, hiring, training, supervising, and firing of the non-clinical personnel; (3) providing and maintaining the premises where the practice operates; (4) purchasing supplies for the practice; (5) bookkeeping and accounting services; and (6) billing and collecting on behalf of the practice.

For those decisions that could implicate professional medical judgment, the PE firm will still try to obtain decision-making authority so long as the physician is ultimately responsible for the decision. In practice, the management services agreement will often require that the MSO be consulted for all decisions regarding: (1) control of patients’ medical records, including determining what is or is not recorded therein; (2) selection, hiring, or firing of physicians, allied health staff, and medical assistants for reasons related to clinical competency; (3) setting the parameters under which the physician will enter into contractual relationships with third-party payers; (4) decisions regarding coding and billing procedures for patient care services; and (5) approving of the selection of medical equipment and medical supplies for the medical practice.

Ensure the Management Fee Bears a Reasonable Relationship to the Services Provided.

To safeguard against the appearance of undue control by the MSO, the management fee should bear a reasonable relationship to the MSO services. This is especially important when part of the management fee is for marketing services (e.g., when the MSO markets the medical services to referral sources such as patients).39 The management fee may be structured using one or a combination of three systems:

- Percentage of Practice Revenue: This fee system helps align the financial incentives of the MSO with those of the PC and is relatively simple to calculate.40 This is perhaps the most common fee system.

- Fixed Fee: This fee is generally permitted but represents a challenge as accurate budgeting is difficult.

- MSO’s Costs Plus Markup: This fee is also generally permitted but may be difficult to administer and may not align the MSO’s financial incentives with those of the PC.

Provider Pitfalls

- Indemnity: For smaller-scale physician practices, the selling physician-owners are often named as parties to the purchase agreement. As a named party, the selling physicians make (in their individual capacity) representations and warranties regarding the practice’s viability and compliance. If the buyer incurred any damages or costs resulting from a breach of these representations and warranties, the selling-physician owners may be obligated to indemnify the buyer for the company’s pre-closing conduct. In practice, personal liability is often not disclosed or discussed during the initial negotiations, and so it can come as a surprise for physician sellers. It is important that physician sellers understand any personal indemnity obligations, and if uncomfortable with the associated risk, limit or remove them.

- Adverse Events: The MSO’s (or its parent entity’s) Operating Agreement will identify the events that trigger the redemption of the selling physicians’ ownership interests. Depending on the triggering event, the redemption price is usually the fair market value of the interests (a “Non-Adverse Event”) or a far lesser amount (an “Adverse Event”). In our experience, the MSO’s Operating Agreement will define an Adverse Event as broadly as possible to justify its redemption of the physicians’ interests for a low price. Common Adverse Events include (1) the termination of the physician’s relationship with the PC or MSO for cause, (2) the physician’s breach of his/her employment agreement, the Operating Agreement, Purchase Agreement, or affiliated transaction document, (3) the termination of the physician’s relationship with the PC or MSO (for whatever reason) before a certain time (more on this below), and (4) the physician’s voluntary withdrawal from the PC or MSO. In the last instance, if the physician decides to end his employment, the MSO could repurchase the physician’s interest in the MSO for an adverse price—sometimes as low as one dollar. While the physician’s negotiating power is rather limited, you can protect the physician’s equity by limiting the definition of an “Adverse Event” to cover only egregious conduct.

- Employment Term and Non–Compete: Sometimes, the PE firm will entice the selling physician to sign an employment agreement with a mutual without-cause termination provision. At first glance, the physician can seemingly terminate his or her employment at any time with advanced notice. However, the physician is usually promised equity in the MSO, and as such, consents to the MSO’s Operating Agreement. As mentioned above, an Adverse Event can include the physician terminating his or her relationship with the PC or MSO—for whatever reason—within a specified period (such as one or more years) from the closing date. Thus, while the physician has the right to leave the PC for any reason under his or her employment agreement, the Operating Agreement inevitably deters the physician from leaving the PC for several years. Moreover, the Operating Agreement almost always restricts the physician’s ability to practice medicine in a specified territory even after this “probationary period” has lapsed. It is in the physicians’ best interests to reduce the “probationary period” and again limit the Operating Agreement’s definition of Adverse Event to allow a physician to terminate his or her employment without cause and without consequence.

Conclusion

Given the complexity of California’s CPOM prohibition, the impacts and outcomes of PE healthcare acquisitions in the State are inevitably nuanced. As California continues to scrutinize and potentially tighten regulations around healthcare acquisitions, PE firms must adapt, and the heavily relied upon friendly-PC workaround may be forced to evolve. The fluctuating regulatory environment may lead to more cautious investment approaches or creative structuring of deals to align with legal requirements.

- Jane Zhu and Zirui Song, Expert Voices: The Growth of Private Equity in US Health Care: Impact and Outlook, NIHCM, (May 17, 2023), https://nihcm.org/assets/articles/NIHCM-ExpertVoices-052023.pdf.

↩︎ - David Blumenthal, Explainer: Private Equity’s Role in Health Care, Commonwealth Fund, (Nov. 17, 2023), https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/explainer/2023/nov/private-equity-role-health-care. ↩︎

- Alexander Borsa, Geronimo Bejarano, et al., Evaluating trends in private equity ownership and impacts on health outcomes, costs, and quality: systematic review, The BMJ (July 19, 2023), https://www.bmj.com/content/382/bmj-2023-075244.

↩︎ - Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Mark A. Hall & Erin C. Fuse Brown, Private Equity and the Corporatization of Health Care, Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance, (Apr. 19, 2023), https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2023/04/19/private-equity-and-the-corporatization-of-health-care/.

↩︎ - Cal. Corp. Code §§ 13400-13410. Accordingly, medical practices cannot incorporate as LLCs, non-professional corporations, or limited partnerships. § 13405; Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code § 2400 et seq. Medical groups can be structured as a general partnership or operate without any corporate form (often referred to as “sole proprietorships”). Cal Bus. & Prof. Code § 2285.

↩︎ - Under the Moscone-Knox Professional Corporation Act, physicians are allowed to incorporate as professional medical corporations, provided the corporations are owned and governed by licensed physicians. Cal. Corp. Code §§ 13406-13407; Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code § 2406. Certain non-physician employees, like registered nurses or physician assistants, are permitted under specific conditions. Cal. Corp. Code § 13401.5; Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code § 2408.

↩︎ - Both stock and asset sales are effectively embraced by the requirement that medical groups incorporate as PC. For example, a lay entity cannot purchase the stock of a PC because lay entities cannot own the stock of a California PC. Similarly, a PE firm could not employ the medical group’s physicians for the purpose of treating patients.

↩︎ - See Epic Med. Mgmt., LLC v. Paquette, 244 Cal. App. 4th 504, 516 (2015) (clarifying Bus. & Prof. Code § 650(b) permits contracts between physicians and non-physicians basing compensation on percentage of gross revenue if fee is commensurate with the MSO’s services being provided). ↩︎

- Hall, supra note 6.

↩︎ - Blumenthal, supra note 2. ↩︎

- PE firms often prefer to create a holdings company that will own 100% of the MSO’s interests. Owning an indirect interest in the MSO via a holdings company, as opposed to owning an interest in the MSO directly, can better facilitate the transfer of ownership or the sale of the healthcare practice and its associated assets. Moreover, separating the MSO from the PE firm’s main operations shields the PE firm from potential liabilities arising from the healthcare practice or the MSO’s operations. This structure can also provide tax advantages by allowing for more flexible structuring of the ownership and distribution of profits. ↩︎

- Frances Nahas and Mark Zitter, Kenan Insight: Private Equity in Healthcare: What the Experts Want You to Know, Kenan Institute for Private Enterprise, (Feb. 10, 2022), https://kenaninstitute.unc.edu/kenan-insight/private-equity-in-healthcare-what-the-experts-want-you-to-know/.

Frances Nahas and Mark Zitter, Kenan Insight: Private Equity in Healthcare: What the Experts Want You to Know, Kenan Institute for Private Enterprise, (Feb. 10, 2022), https://kenaninstitute.unc.edu/kenan-insight/private-equity-in-healthcare-what-the-experts-want-you-to-know/.

↩︎ - Improving Medical Technologies: Private equity’s role in life sciences, American Investment Council, (Mar. 2022), https://www.investmentcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/aic-life-sciences-report2-1.pdf.

↩︎ - Nirard Jain, et al., Healthcare Private Equity Market 2023: Year in Review and Outlook, Bain and Company, (Jan. 3, 2024), https://www.bain.com/insights/year-in-review-global-healthcare-private-equity-report-2024/.

↩︎ - Zhu, supra note 1.

↩︎ - Joe Aguilar & Natalie Bell, Knock, knock… Who’s there? Considerations for when private equity comes for physician acquisitions, Insight Article, (Jan. 1, 2024), https://www.mgma.com/articles/considerations-for-when-private-equity-comes-for-physician-acquisitions.

↩︎ - Yashaswini Singh, et al., Association of Private Equity Acquisition of Physician Practices 2022, JAMA 3(9):e222886 (2022), available at https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama-health-forum/fullarticle/2795946.

↩︎ - Ibid.

↩︎ - Ibid.

↩︎ - Joseph Doy Bruch et al., Workforce Composition in Private Equity–Acquired Versus Non–Private Equity–Acquired Physician Practices, Health Affairs 42, no. 1 (2023), available at https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00308.

↩︎ - Richard M. Scheffler, et al., Monetizing Medicine: Private Equity and Competition in Physician Practice Markets, American Antitrust Institute, (July 10, 2023), https://www.antitrustinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/AAI-UCB-EG_Private-Equity-I-Physician-Practice-Report_FINAL.pdf.

↩︎ - Sneha Kannan et al., Changes in Hospital Adverse Events and Patient Outcomes Associated With Private Equity Acquisition, JAMA 330(24) (2023), available at https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/2813379.

↩︎ - S.B. 977, 2019-2022 Reg. Session (Cal. 2020).

↩︎ - A.B. 3129, 2023-2024 Reg. Session (Cal. 2024).

↩︎ - S.B. 184, 2021-2022 Reg. Session (Cal. 2022), codified at Cal. Health & Safety C. § 127500 et seq.

↩︎ - See https://hcai.ca.gov/about/laws-regulations/#health-care-affordability.

↩︎ - 22 C.C.R. § 97431.

↩︎ - A material change transaction occurs if a healthcare entity meets one of the eight thresholds enumerated under 22 C.C.R. § 97435(c), such as a transaction that results in transfer of control or governance, a transfer of a significant portion of assets, or a likely increase in annual revenue of $10 million or 20%.

↩︎ - 22 C.C.R. § 97440(a)(2).

↩︎ - 22 C.C.R. § 97442.

↩︎ - 22 C.C.R. § 97442(b).

↩︎ - 22 C.C.R. § 97442(c)-(d).

↩︎ - People ex rel. Allstate Ins. Co. v. Discovery Radiology Physicians, P.C. (Super. Ct. Los Angeles County, Nov. 5, 2020, 20STCV42672); People ex rel. Allstate Ins. Co. v. OneSource Medical Diagnostics, LLC (Super. Ct. Los Angeles County, Nov. 24, 2020, 20STCV45151).

↩︎ - People ex rel. Allstate Ins. Co. v. Discovery Radiology Physicians, P.C. (2023) 94 Cal.App.5th 521, review denied (Nov. 21, 2023).

↩︎ - American Academy of Emergency Medicine Physician Group, Inc. v. Envision Healthcare Corporation (N.D. Cal., Dec. 20, 2021, No. 22-CV-00421-CRB).

↩︎ - Ibid.

↩︎ - See Epic Medical Management, LLC v. Paquette, 244 Cal. App. 4th 504 (2015) (court rejected physician’s argument that some management fee payments to MSO constituted illegal kickbacks for MSO’s marketing services in which some patients were referred to physician through marketing activities, finding no illegal payment for referrals occurred because management fee was commensurate with services rendered).

↩︎ - Unlike some other states, California does not consider this fee system to violate anti-kickback law so long as the fee “is commensurate with the value of the services furnished[.]” Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code § 650(b).

↩︎